Imprints: Exhibitions That Linger in My Mind

Royal Academy of Art - Kiefer/ Van Gogh

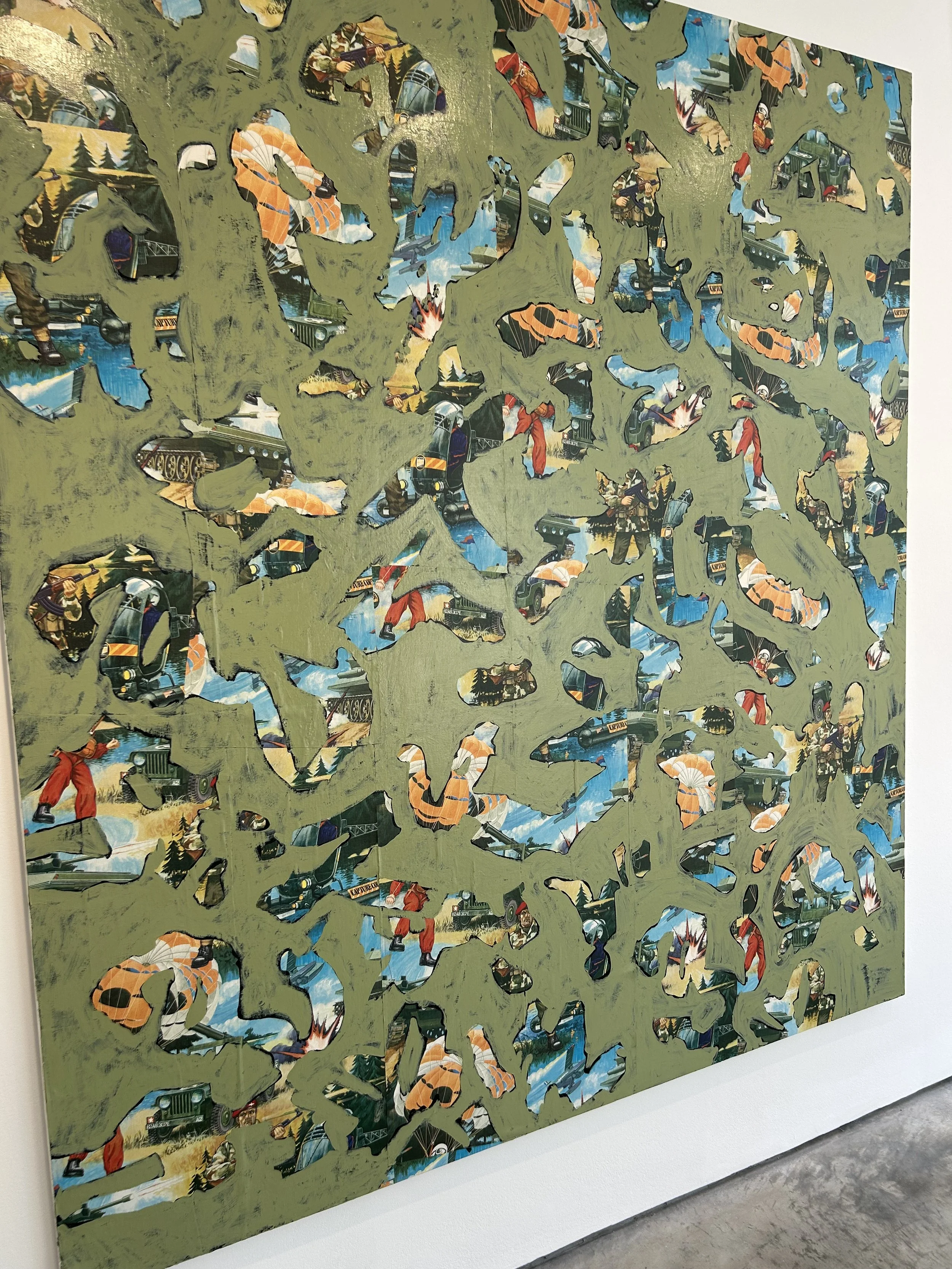

Walking into the exhibition, one is immediately struck by the sheer scale and textural density of Anselm Kiefer’s works. Their monumentality commands attention, evoking violence, memory, destruction, an instant confrontation with history. Kiefer, a giant of contemporary art, imposes himself heavily across the exhibition rooms.

The curatorial frame suggests a dialogue between Kiefer’s late landscapes and one of his earliest influences, Vincent van Gogh. Yet the comparison feels strained. Where Van Gogh’s canvases speak through intimate brushstrokes, subtle colour, and dreamlike sensitivity, Kiefer overwhelms. His landscapes blare rather than whisper, offering little of the nuance or fragility that characterises Van Gogh’s vision.

Kiefer’s burning wheat fields, scorched earth, and symbolic detritus undoubtedly recall the horrors of WWII and the scars of history. But next to Van Gogh, who painted suffering, madness, isolation, and poverty with visceral honesty, Kiefer falls short. His canvases lean towards theatrical display: golden hues and teal washes verge on the decorative, while his monumental sunflowers risk becoming pastiche, borrowing Van Gogh’s motifs as memorabilia.

What Van Gogh distilled from within, raw emotion, turmoil, a fragile sensitivity, Kiefer externalises in loud, referential gestures. His works cite Greek tragedy and Heidegger, yet at times feel weighed down by their own intellectual scaffolding. The result is less a channeling of lived experience than a performance of gravitas.

Kiefer may aim to wrestle with history, but beside Van Gogh’s radical brushstrokes and aching humanity, the noise begins to drown out the feeling.

Lisson Gallery - Finding the Blue Sky by Omar Kholeif

Omar Kholeif is one of my favourite curators working today, so when I saw he was curating an exhibition at Lisson Gallery featuring some of my favourite artists, including Huguette Caland and Anuar Khalifi, I jumped at the chance. As Kholeif writes, “The show is my love-letter to London, a city that I have continually returned to over the last four decades. It is a journey of retreat and surrender that will be familiar to millions in search of a sense of longing and belonging — of home, of sacred space. Finding My Blue Sky invites spectators to indulge in the sensuous curve of artistic endeavours that exist in their own culturally situated space of dreaming—one that allows us to sketch myriad possible routes to modernity, and with this, new ways of looking altogether.”

Finding My Blue Sky struck me as both a deeply personal and profoundly collective gesture, a curatorial weaving of memory, longing, and displacement into a tapestry of voices that felt at once intimate and expansive. What I found most compelling was the way the exhibition dissolved the boundaries of the gallery itself, spilling into streets, windows, and courtyards, as if insisting that questions of belonging and identity cannot be contained by white walls.

At times, the density of works risked overwhelming the viewer, but this very multiplicity seemed intentional: a refusal of singular narratives in favour of layered, polyphonic encounters. The range of mediums, sculpture, painting, sketches, added to this sense of abundance. Walking through, I sensed Kholeif’s “love letter to London” not as a static homage but as an ongoing conversation, one that prompted me to consider my own dreams of elsewhere, my own imagined blue sky.

Political, personal, and cultural, the exhibition left me reflecting on the parallel title in Arabic, which carries a distinct inflection: “What is the world that you dream of?”

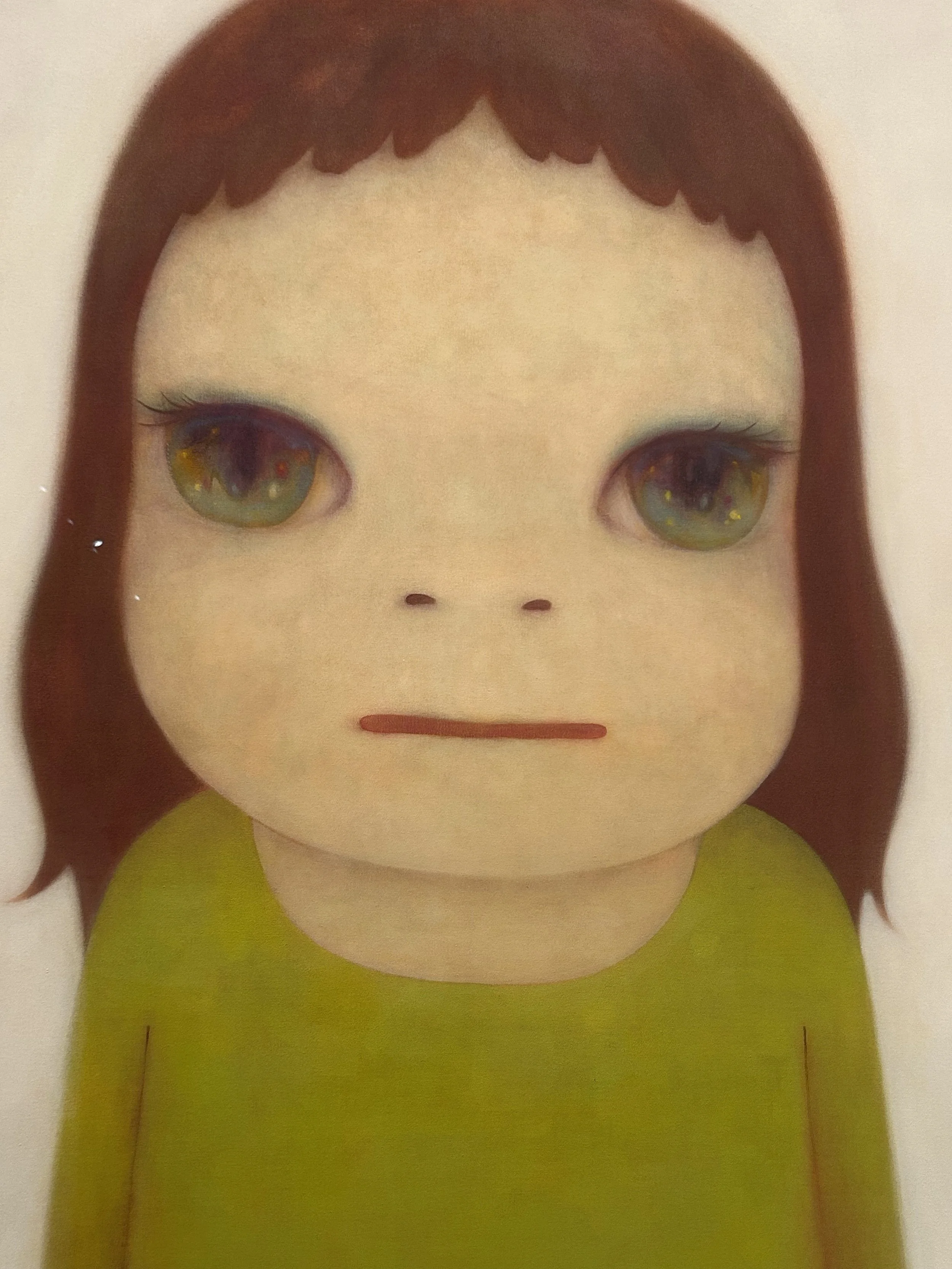

Hayward Gallery - Yoshitomo Nara

I think this was, singlehandedly, the most memorable and captivating exhibition I experienced in 2025. I felt transported into a world where fragility and defiance coexist, distilled through the deceptively simple yet eerily cute figures of children that have become Nara’s signature. What struck me most was how the installation encouraged a slower, more contemplative gaze: the paintings, drawings, and sculptures radiated a quiet intensity that resisted the speed of contemporary viewing habits. I found myself drawn, almost engulfed, into their inner worlds: their turmoil, anger, disappointment, and sensitivity. In a single expression, a glance, a smirk, an entire system of destruction seemed to be divulged.

The atmosphere was tinged with melancholy yet carried an undertone of resilience, as if Nara were offering a space to confront both vulnerability and strength in equal measure. While the repetition of motifs risked a certain predictability, the cumulative effect was undeniable, transforming the gallery into a psychological landscape where memory, solitude, and tenderness unfolded with striking clarity.

The curatorial approach was simple yet deeply effective: visitors entered a childlike world, beginning with a small playhouse and an impressive display of vinyl records, both evoking the inner mind of adolescence and the process of coming of age. These images remain with me, imprinted and unforgettable.

Serpentine Museum - The Call by Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst

Holly Herndon’s project at the Serpentine unfolded less like a conventional exhibition and more like an experiment in what collective authorship and machine collaboration can mean today. Entering the space, I felt caught between the intimacy of the human voice and the unfamiliar presence of AI-generated sound, the two entwining until it became difficult to separate origin from echo. What impressed me most was how Herndon foregrounded participation, the sense that the audience was not just listening but implicated in the act of co-creation, their presence shaping the work as much as the algorithms did.

At times, the conceptual density risked overshadowing the affective charge, yet the overall effect was one of porousness and invitation, a challenge to rethink creativity not as an individual act but as a distributed, communal process.

Tate Modern - Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider

Visiting Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider at Tate Modern alongside my Courtauld seminar group was an invaluable chance to experience the vibrancy of German Expressionism beyond our seminar texts. Kandinsky, Münter, and their circle reimagined painting as a spiritual and emotional language, abandoning representation in favour of bold colour, flattened forms, and an almost musical rhythm of line and shape. Encountered in person, Kandinsky’s abstractions seemed to hum with inner sound, while Münter’s landscapes conveyed a crisp immediacy that underscored her distinctive contribution.

Central to the exhibition was the influence of sound and performance, an aspect that connects directly to my own research at the Courtauld. I was particularly struck by how the show foregrounded women artists so often overlooked in Expressionist histories, from Münter’s photographs to the dramatic canvases of Marianne Werefkin. Kandinsky’s writings on The Yellow Sound also felt newly vivid within this context: his non-representational compositions unfolded like scores for the eye, resonating with Schoenberg’s dismantling of tonal harmony to expose raw psychological intensity. The canvases pulsed with rhythm and dissonance, embodying the same spirit of rupture and reinvention that defined Expressionist music.

Overall, the exhibition offered an impressive array of artists, styles, and dramatic visions, a testament to the lasting influence and power of the Blue Rider group.

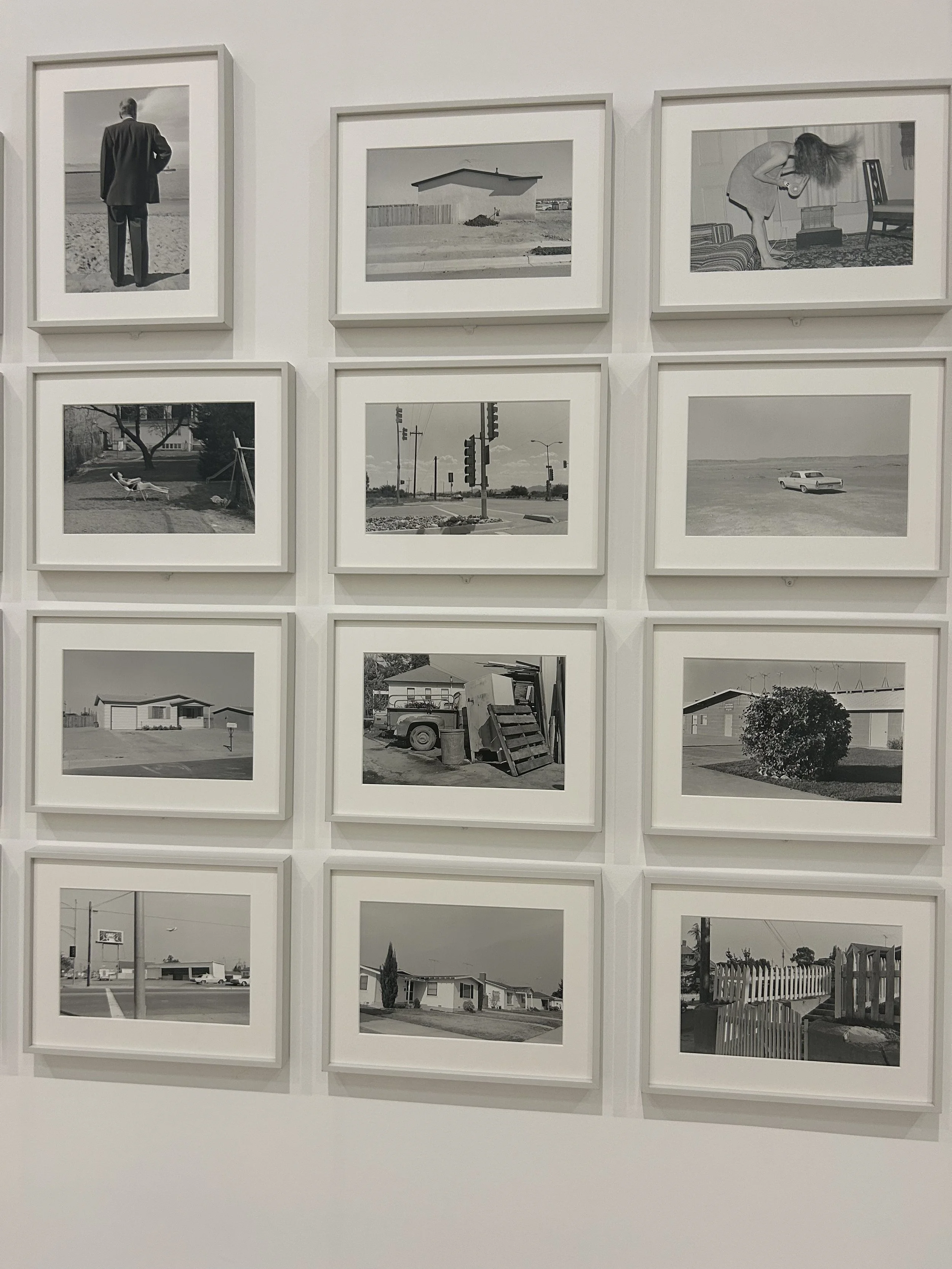

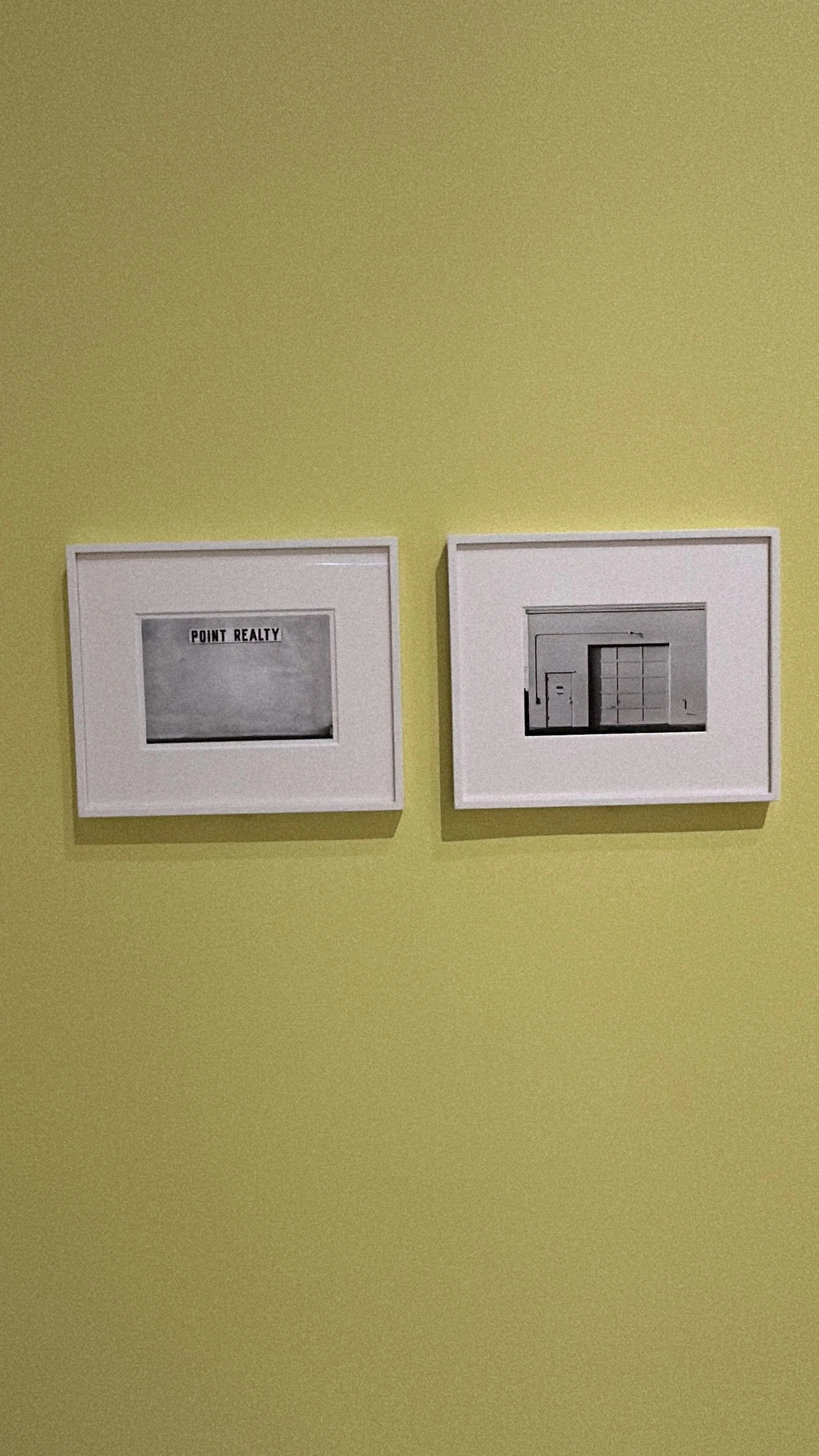

Rencontres d’Arles 2024

Immersed in the city’s historic sites, I encountered exhibitions that revealed how photography can hold memory, rupture, and experimentation in equal measure.

Randa Mirza’s Beirutopia stood out for the way it layered documentary and poetic registers, contrasting glossy construction billboards with the ruins of Beirut to expose the fictions of progress and the persistence of absence. In contrast, I’m So Happy You Are Here: Japanese Women Photographers from the 1950s to Now offered a wide-ranging intergenerational perspective, highlighting overlooked voices such as Ishiuchi Miyako, Rinko Kawauchi, and Yurie Nagashima, whose works reimagined both the everyday and the role of women in photographic practice.

Moving between medieval cloisters, industrial spaces, and contemporary galleries, I began to grasp how context and curation transform meaning, and how exhibitions themselves can become conversations across histories and geographies. This experience gave me a first sense of how to think critically about art in situ, and it laid the groundwork for the way I approached my studies at the Courtauld and my current curatorial approach, attentive not only to artworks but also to the networks of history, space, and audience that shape their reception.